I’m Not Brave (I’m Weird and Embarrassing)

By Danielle Tcholakian

Sometimes you write an essay about getting sober or surviving depression or not being very attached to being alive, and people tell you that you’re “brave” for having done so. And while on a good day, about 70 percent of me can believe they mean it as a compliment, the obvious subtext I hear is, “Wow, I would not have written something so weird and embarrassing.”

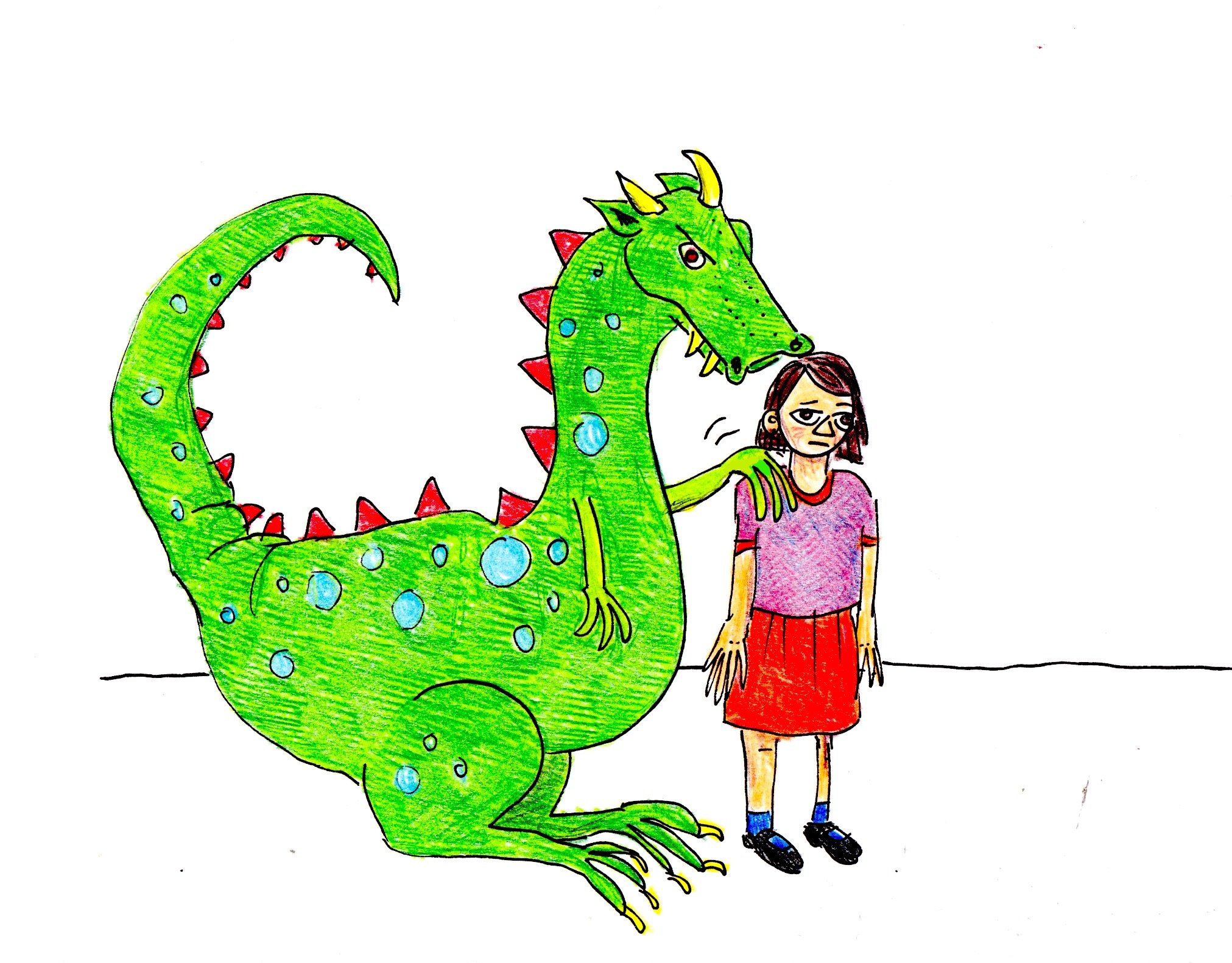

A friend of mine sometimes gets called brave for writing things that aim at influential people–like crooked politicians who amass and hold onto power or “good guys” who aren’t actually very good. She tells me that she feels alone and more than a little angry when she gets called brave in that context. She believes people are saying to her, “We’ll watch you slay these dragons and privately tell you that all that dragon-slaying you’re up to is brave. We know these are bad guys, but we’ll let you keep standing there alone.”

I only really hear “brave” in response to personal writing when I do presumably ill-advised things like write about accidentally fucking a probable insurrectionist. Generally, the only dragons I’m slaying are decorum and my own dignity.

People will explain: no, what we mean is your vulnerability. Your openness. Yes, I will think. The saying of things that you don’t really think should be said.

Here is the truth: I cannot be vulnerable or open and honest when in a relationship with a real live person. Sometimes, it feels like fundamentally even just being myself with ease or sometimes even at all. I can absolutely be vulnerable on the internet to many strangers I never have to look in the eye. But looking at a real person in the eye—for instance, someone I’m supposed to be intimate with—is difficult mainly because I don’t want to tell them how I feel: I am afraid almost all of the time. That my body is, I think, more fear than blood or water. And, especially, “I am afraid you will one day behave differently than you are now.”

Terrifying. Hard pass. Absolutely not.

Soon I will help facilitate a community conversation on anti-racism at the public library where I work. We’re planning to prepare people to identify and deal with possible “triggers.” One of the questions in this group setting is, “What do you know to be the wound this trigger originates from?”

I helpfully volunteered to answer these difficult questions first. “You can call on me,” I said. “I have a lot of practice being vulnerable. I’ll do it just fine.”

Except the truth is, I don’t.

I have some practice being vulnerable to No One (a faceless, nameless internet) and also Everyone (on the internet, which means about as much as No One). I have some practice being vulnerable on my computer screen, looking into a Zoom window with a bunch of little boxes where kindly faces look back at me, where I have the comfort of knowing we are all here because we are fundamentally made of fear.

I have practiced being vulnerable, if by vulnerable, we mean self-effacing, goofy, and jokey, so I won’t go home and ruminate over whether I was annoying or burdened people, whether I grossed them out, whether I made myself less attractive to them than they previously found me. Because the truth is, I have worked really, really hard to not dislike myself so much, but I still worry, sometimes in an acute, frightened, little-kid way, about being Too Weird and maybe even Scary.

*****

When I was in 7th grade or 8th grade, I wrote this earnest letter to the cast of the Broadway show RENT. I watercolored a piece of paper and then typed out the letter and then cut out the lines of the letter and pasted them on, and god, I cringe just thinking about it.

The letter accompanied a donation to a fundraiser the cast was doing, and I was so eager to tell them how much their art meant to me, I said something like, “Your show makes me want to be alive!” believing that there must be nothing better to hear, as an artist.

Someone from the cast of RENT called my house—I put my home phone number on the letter in the desperate hope that they might want to call and thank me and invite me to hang out backstage. But instead, the cast of RENT called my mom and told her how the letter worried them.

And in my memory, my mom laughs and says something mollifying, possibly about me being “intense,” and then I remember–and this is the thing that still cuts me–that I intuited they didn’t want to talk to me, or maybe she asked, and I could tell they said no? Either way, I never spoke to the cast of RENT. They never invited me backstage, they never befriended me, and they never invited me up on stage to take a bow with all of them after a show.

Instead, my mom told me I needed to be more careful not to freak people out. We don’t have to tell strangers everything about ourselves or something similar about not being overwhelming to others. And I felt so utterly crushed.

I thought about the memory a lot in early recovery when all the shit I’d been running from for 20 years felt so raw and immediate and intense. And as I started approaching a year sober, something remarkable happened: Increasingly, my impulse to cringe was pushed aside by a sort of retroactive protective anger. Instead of thinking about that middle school version of myself as this fucking oversharing loser, I think about what a sweet kid that was, to want to connect, to reach out as a human among humans, to believe in humanity and in goddamn art enough to assume that my experience must be shared by, or at least understandable to, people connected to art that mattered to me so much.

And I want to cover her ears during that phone call or distract her somehow, pull her away, so she doesn’t witness it, even one-sided. I want to protect her from being told to hide, that who she is and how she’s inclined to behave by nature is embarrassing and weird and too much. I want to say to her, even though I know it’s honestly probably bad advice, to be her fucking self exactly as she is for fucking ever, and that anyone who finds that “overwhelming” or “uncomfortable” is a fucking loser-coward who isn’t worth alone goddamn minute of her most boring day. Being honest and vulnerable is the bravest thing a human can do, and she had more strength and courage in one goddamn fingernail than any adult in her life had in their whole body. I’m sorry for how uncomfortable and scary and lonely that is, but it’s also okay. It’s going to be complicated. Sometimes it’s going to be really fucking hard. But it will be okay. It will all be okay.

*****

Last week, one of the teens I work with at the library, who is helping plan this anti-racism discussion, was looking through a box of old zines of mine, and I heard her gasp. I looked over, and she was holding an old Playbill for RENT. I reached in and pulled out eight more, told her how I used to go get cheap lottery tickets and watch the show on weekends when I was about her age. “That’s so unfair,” she said. She was jealous. I started to move on to a different task, then I told her about the letter laughing. About the weird, embarrassing letter my weird, awkward teen self sent and how it was received. She laughed along with me, but then I said, tentatively, that I think maybe it wasn’t so embarrassing. That I think, looking back, that was pretty brave and pretty cool, to be young and honest and open and to care so much. And she stopped laughing and said, without hesitation, “I don’t think you should be embarrassed.”

We moved on pretty quickly, her returning her attention to unearthing this trove of artifacts from when this grownup in her life was her age, me to whatever my task was. But that brief little interaction healed a wound I’d been carrying around. I sometimes worry that the very thing that compels me to be a Grownup For Teens, the fact that I still feel very connected to my teen self is something that makes me not really a very good Grownup (for Teens, and maybe in general).

I worry about my boundaries not being firm enough, about not being Sure Enough of things they might need me to be Sure about, about replicating some of the shitty grownup behavior I experienced from grownups who mistook my precocity for a sign to tell me more than they should have, to be inappropriate with me in ways that were subtle and confusing, probably to both of us, but that fucked me up. I really, really, really don’t want to fuck these kids up.

Back then, I trusted grownups more than kids because I felt weird. Like I couldn’t fit in with other kids because my desire for the approval and love of my peers was ravenous and my sense that I knew how to be a teenage person in the world was absolutely nonexistent, and that was so scary to me. Grownups were safer, or at least they had been up until then. The idea of grownups, especially grownups not in my family, was a fantasy that hadn’t yet been spoiled. But I think some of that anger at myself was that teenage version of me thinking, “See? This is why no one likes you. This is why you can’t fit in. This is why you’re not cool? See? Fucking embarrassing. Fucking loser.” I was being mean to myself before anyone else could shock me with a meanness I hadn’t anticipated.

And then this teenager seemed to look right at the sad, scared teenager inside me and say, “Nah. That’s so cool. That’s so cool that you wrote that letter.” And for the first time in more than 20 years, something inside me relaxed, calmed down, rested. Was accepted–felt accepted. And maybe, just maybe, for once, a little brave.

*****

Danielle Tcholakian is a writer and Jezebel columnist who lives in the Finger Lakes. Her Tweets are here.

If you like this story, please pass it along. If you’d like to donate, press the box below.