We’ll Make Great Pets

“In a wine-drunk fugue state, I’d sent half a dozen emails to a Korean woman I’d never met, demanding that she PayPal me 500 American dollars, or else I would give the cat away.”

Today’s essay, from writer Meaghan Garvey, is both a recovery story and a love story. These genres typically overlap, sometimes disastrously, but her spin on them is truly delightful. There are damaged and dishonorable men, of course, but there is also a cat named Breakfast:

“We were similar, Breakfast and I — private, independent, except for when it came to the objects of our affection; in my case, a revolving door of brooding, damaged men, and in her case, me. She only minorly protested when it came to being zipped into her travel bag and carried through the airport, what with my brilliant decision to quit my job and move to Texas with a long-haired piano player I’d met in a late-night bar. Then back into the bag and to the airport yet again after another tequila-fueled blowout in which things had been said that could not be taken back. Shepherding the stoic creature through security at Austin-Bergstrom, my heart exploded with a protective tenderness I had assumed would be reserved for one’s own children. “I will bring you home,” I promised. “You can count on me.”

I asked Meaghan if this story was tough to write.

“This story was hard to write, I suppose, in that I am always wary of appearing to romanticize my various lifestyle delusions over the years. These same delusions are a continuing source of inspiration, though, so it’s all good in the end. I did shed a tear or two throughout the writing process for my cat, who passed away one month ago today, and whom I miss very much.”

Be sure to share this story — I’m opening up comments, too, so if you have one (a polite, supportive, de-fanged one) please add it into the mix.

*****

Btw: We’d love to publish more stories like this. We were able to pay Meaghan thanks to the money from paid subscriptions. We want to do more of these this year and we love it if you could help us achieve that goal.

Also, we make a great gift.

Breakfast: A Cat Story

A pet unwittingly inherited after a chaotic, doomed relationship turned out to be the greatest gift of my adult life — and a sign that a different path was possible.

Written by Meaghan Garvey

*********************************

Edited by Steve Kandell

Illustrated by Edith Zimmerman

I met my cat in 2016, the first time I went to Tony’s apartment in Silver Lake. A formerly iconic music news network, then in what you might call a “rebuilding era,” had sent me to L.A. to interview an up-and-coming R&B singer, whose team stopped returning my emails and calls no sooner than I’d arrived. In any case, my hotel room was booked for five days. I hesitantly typed a message to my most mysterious reply guy, whose profile picture was a face shrouded in smoke, black hoodie pulled tight over what looked like a shaved head. For months he’d frequented my DMs with late-night messages about the superior artistry of Justin Bieber, or his plans to move from L.A. to Joshua Tree, where he would buy a Vespa with a basket for his Siamese cat, Breakfast, as well as several firearms he admired “from an engineering standpoint.” “You can visit me,” he offered. I said, “Oh, I don’t know . . .”

I sat there for a while in the darkening hotel room with the message typed out, then finally hit send. “Dude come over,” Tony replied something like 30 seconds later. He was packing for the desert, leaving any day now. “I’ve got a bottle of soju,” he assured me, “and some mushrooms.” He lived around the corner from the mural on the cover of the Elliott Smith album Figure 8.

I remember how he looked then, standing in the lobby in track pants and Adidas slides: 6’0” with bad posture, a nose that clearly had been broken more than once, and tattoos that spelled “SCUM” across his knuckles, two letters per hand. His studio was empty: no furniture, no bed, just some cardboard boxes and a Bass Station keyboard. The little Siamese cat chased him around the room as he poured soju into teacups, pulled mushrooms from a freezer bag. He put on his own music, an edit he had made in homage to David Bowie, who had died the month before: “Five years, my brain hurts a lot, five years, that’s all we’ve got . . .” There wasn’t a lightning-strike moment, a flash of falling in love. We already were.

My debit card got flagged for fraud, so when the hotel stay was up, we booked two more nights in cash. (“Just wanted to make sure you made it back okay,” emailed the company’s production coordinator. “We got the notification you didn’t make the car pickup. Assuming you took a cab from the airport?” I didn’t reply.) Then we ran out of cash. I used my dad’s Southwest miles to book a flight back home. That night in his empty studio, we watched a movie where a mutt is sold to a dog-fighting ring, trained to kill. Tony sobbed through the whole thing. The cat nestled between us on the carpet where we slept. I had lost my state ID card at some point along the way, but at LAX the next day, they just let me walk right through.

Two weeks later, he and Breakfast had moved across the country and into my Greenpoint sublet, bringing the census to four adults, three cats.

˗ˏˋ ★ ˎˊ˗

In a wine-drunk fugue state, I’d sent half a dozen emails to a Korean woman I’d never met, demanding that she PayPal me 500 American dollars, or else — and she could pass along the word to her new boyfriend! — I would give the cat away. It was December 2017, Chicago, a few weeks after Tony had shipped off to South Korea — to “find himself,” he’d said, though of course I knew the truth, leaving me with Breakfast until his (LOL) “return.” It wasn’t his new girlfriend’s fault, nor had I any real intention of abandoning the creature who, despite her preference for her now-absent father, I liked having around. But my pride had been wounded, my trust had been betrayed, and I was drinking to the point of blackout several times a week, waking up to emails from the Korean woman politely declining my attempts at extortion.

The cat seemed interested in my strange behavior, joining me on the balcony for bitter chain-smoking sessions or weaving through the tangled cords of the tattoo machine I’d bought on Amazon Prime, which I’d usually forget about ’til after 2 a.m., when inspiration was known to strike while listening to the maudlin tunes of yesteryear. “Love hurts!” Roy Orbison would warble, and I’d agree — “That it does, Roy!” — as I dragged the hissing needle across my arm or thigh, not out of masochism but confused creative impulse, like if I just expressed myself, someone would surely understand. (What I mean by “understand” is “fall madly in love with me, preferably at first sight.”) At some godforsaken hour we’d retire to bed and the cat would wedge herself comfortably between my legs, undaunted by my bullshit, maybe even amused.

We were similar, Breakfast and I — private, independent, except for when it came to the objects of our affection; in my case, a revolving door of brooding, damaged men, and in her case, me. She only minorly protested when it came to being zipped into her travel bag and carried through the airport, what with my brilliant decision to quit my job and move to Texas with a long-haired piano player I’d met in a late-night bar. Then back into the bag and to the airport yet again after another tequila-fueled blowout in which things had been said that could not be taken back. Shepherding the stoic creature through security at Austin-Bergstrom, my heart exploded with a protective tenderness I had assumed would be reserved for one’s own children. “I will bring you home,” I promised. “You can count on me.”

She projected her distaste when a new boyfriend would sleep over, or when the neighborhood bar stars would come by late at night for one more round after last call — fellow gregarious Midwesterners with an air of tragedy, for whom the notion of sitting alone with their thoughts for 15 minutes registered as some kind of Promethean punishment. For the first time in adulthood I had found community in the place I lived and not online, hanging around the taverns of Chicago’s far north side. The regulars told better stories than the autofiction novelists and try-hard cultural critics whose debuts were sold to me as urgent, necessary reflections of our time. As if “our time” wasn’t precisely what I was avoiding, whiling away the days and weeks not answering my emails, crushing Old Styles with divorced boomers losing their teeth.

The idea did not entirely escape me that, statistically and anecdotally, I had what some would maybe call a drinking problem. “Meet you tomorrow for Jeopardy!” I would text my tavern friends, which is how you launder your desire to drink at 3PM. But was it possible, I wondered, that I brought to alcoholism a certain writerly panache? Almost every writer I admired had drank themselves to at least temporary ruin — Denis Johnson, Lucia Berlin, Marguerite Duras, to say nothing of Hemingway, in whose hometown I was born. And anyway, it wasn’t like I woke up shaking. The story was the thing.

˗ˏˋ ★ ˎˊ˗

It must have happened overnight somewhere in my mid-thirties — with no alarm clock or intention, I started waking up at sunrise or sometimes well before, making coffee, and writing for hours while the neighborhood was quiet, save for the mourning doves. For more or less a decade I had called myself a writer, but I’d only felt satisfaction in the work when it was done and I could fuck off to the bar, where no one knew what Pitchfork even was. Now I felt driven by a force beyond a deadline, or even a compulsion; the routine of the writing had become the joy itself. So much did I look forward to my little morning ritual — during which the cat would enjoy her namesake meal, then stare at me with one eye open, half-napping on the couch — that I began going to bed around 9 or 10 PM. “Where’s my kitty?!” I would call into the dark, and she’d gallop through the door to fling herself into my arms.

I suppose it hadn’t crossed my mind that you — okay, that I — could be inspired by feeling good the way I could from feeling bad. Or perhaps it hadn’t clicked that feeling good was on the table in ways that didn’t require escapism — from loneliness, conflict, responsibility, myself. Suddenly a hangover was not a fact of life, but a tedious distraction from my daily purpose. So I started drinking less, down to every other night, then maybe once a week. I stopped procrastinating, and found that previously insurmountable tasks such as “opening emails” were not as daunting as they’d seemed. For the first time in forever, I had time to really read; between books and my own life, serendipitous connections appeared to electrify my days with little jolts of chance and intrigue. Was I bored? Maybe a little. Lonely? Not at all. I couldn’t even conceive of sharing my precious solitude with anyone but Breakfast, with whom I shared the kind of love I’d tried so hard to find in men — solid, unwavering, content.

I admit to being wary of sobriety as a concept — possibly out of fealty to my remaining delusions with regard to storytelling, adventure, “everything in moderation.” Unfortunately for whoever will one day inherit my fortune, my prized possessions are the stories, true and otherwise, that you only hear in bars. I guess I always kinda thought that if I hung around for long enough, I’d write the great American novel, purely by osmosis. Sometimes I read the classics of alcoholic fiction for a vicarious thrill: Charles R. Jackson’s The Lost Weekend, Leonard Gardner’s Fat City, the stories of Jean Rhys.

But the truest story I’ve read about bars is “Out on Bail” by Denis Johnson. The bar where the narrator goes is The Vine, a long and narrow room like a stationary train car where men in hospital bracelets swindle the barkeep with counterfeit money. “The Vine was different every day,” the narrator says. “Some of the most terrible things that had happened to me in my life had happened in here. But like the others I kept coming back.” Then many years pass, and The Vine is torn down in the name of “urban renewal.” On the outs with his girlfriend, the narrator walks the streets until he finds another bar that’s open. His old friend from The Vine is there, drinking beside him in the mirror. “There were some others there exactly like the two of us, and we were comforted,” he says. He’s remembering this, years later. “Sometimes what I wouldn’t give to have us sitting in a bar again at 9:00 a.m. telling lies to one another, far from God.”

As Breakfast wrestled with her favorite toy (a woven Navajo placemat) in summer 2024, something caught my eye — a lesion on her stomach that jangled my nerves. A biopsy revealed stage three mammary cancer, which we could maybe hope to mitigate with a mastectomy. The price tag was outrageous, maybe three times what I’d spent on my own healthcare over the course of 30-something years of life. But there was no question I’d pay it. A couple months before, I had received word from his family that Tony had died under circumstances almost too nihilistic to bear. It struck me now that when he’d left me with the cat all those years ago, he’d given me the greatest gift of my adult life. Back at home after the surgery, stitched from top to bottom and faded on pain pills, Breakfast would wrap herself around my neck and press her face to mine through the recovery cone, and we’d lay there for hours together, just breathing.

Six months had passed of what I thought was her recovery when she stopped eating, and tests revealed the cancer had spread. I cried off my fake eyelashes as we cuddled in bed, her breath coming shallow and fast. With the window open, she could hear the sounds of spring, the purr of mourning doves nesting on the AC unit, and as she sat there in a sunbeam with her eyes closed, I knew she understood the situation. “Thank you for being my friend,” I said, and she hugged me one last time. I walked to the bar that evening, looking for that old way out. But it wasn’t there anymore. The old-timers had been replaced by a new cast of characters with whom I’m sure I could have found something to talk about for the next, I don’t know, 15 years. Instead I smoked a cigarette, and then I walked back home.

*****

Meaghan Garvey is a writer from Chicago. Her work has been featured in Billboard, The New York Times, NPR, New York magazine, and in her newsletter Scary Cool Sad Goodbye.

More Featured Essays:

Notes From an Adult Child of Alcoholics

"They were always drinking, as far back as I can remember, in a way that I can now recognize as problematic, but at the time it was just the way things were. As we got older, the drinking got worse. Slowly, then faster and faster, our family lost all of the things that people lose to addiction: jobs, licenses, money, relationships, health. By the time we left for college, the drinking had taken over everything. It burned all the oxygen in the room."

*****

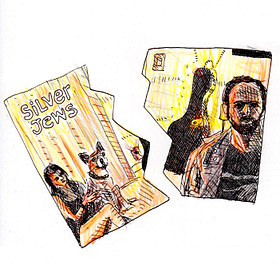

The Alcoholic's Playlist Is Full of David Berman

"On my last drinking day, I wrecked a 6,000-pound truck in a heavily populated area, and somehow I didn’t injure anyone. I went to jail, but not prison. A few days later, just before I went to rehab, I found written in my pocket notebook, “Why doesn’t anyone know how sick I am? Why doesn’t anyone care?” in giant letters across two pages, hand-shredded them and buried them under the wet food trash. If I’d died the same day as David, it would have been my suicide note."

*****

Lather. Rinse. Relapse.

"I was in that ugly little uncomfortable too-bright airport bar right next to security in LaGuardia, on my way back to school in Kansas City, texting my boss so that he wouldn’t call me on the phone and hear the beer in my voice."

ZOOM MEETING SCHEDULE

Monday: 5:30 p.m. PT/8:30 ET

Tuesday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Wednesday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Thursday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET (Women and non-binary meeting.)

Friday: 10 a.m. PT/1 p.m. ET

Saturday: Mental Health Focus (Peer support for bipolar/anxiety/depression) 9:30 a.m. PT/12:30 p.m. ET

Sunday: (Mental Health and Sobriety Support Group.) 1:00 p.m PT/4 p.m. ET

*****

If you don't feel comfortable calling yourself an "alcoholic," that's fine. If you have issues with sex, food, drugs, codependency, love, loneliness, and/or depression, come on in. Newcomers are especially welcome.

FORMAT: CROSSTALK, TOPIC MEETING

We're there for an hour, sometimes more. We'd love to have you.

Meeting ID: 874 2568 6609

PASSWORD TO ZOOM: nickfoles

Need more info?: ajd@thesmallbow.com

This is The Small Bow newsletter. It is mostly written and edited by A.J. Daulerio. And Edith Zimmerman always illustrates it. We need your support to keep going and growing.

We send it out every Tuesday and Friday. For $9 a month or $60 per year, you also get a Sunday issue and access to the full TSB archives.

If you'd like to check in with me and learn more about our recovery meetings, here's where I can be reached: ajd@thesmallbow.com

Also, follow us on Instagram for updates and more illustrations from Edith.

Or you can support Edith directly!

Demon With Watering Can Greeting Cards [Edith’s Store]

Everything helps.

A POEM ON THE WAY OUT:

Heat

by Denis Johnson

*********

Here in the electric dusk your naked lover

tips the glass high and the ice cubes fall against her teeth.

It's beautiful Susan, her hair sticky with gin,

Our Lady of Wet Glass-Rings on the Album Cover,

streaming with hatred in the heat

as the record falls and the snake-band chords begin

to break like terrible news from the Rolling Stones,

and such a last light—full of spheres and zones.

August,

you're just an erotic hallucination,

just so much feverishly produced kazoo music,

are you serious?—this large oven impersonating night,

this exhaustion mutilated to resemble passion,

the bogus moon of tenderness and magic

you hold out to each prisoner like a cup of light?

— “From The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly via Poetry Founation”.

"Sometimes what I wouldn't give to have us sitting in a bar again at 9:00 a.m. telling lies to one another, far from God."

That line touched my soul deeply and brought back so many memories.

I'm grateful for the sobriety that I have today.

Meaghan you’re brilliant